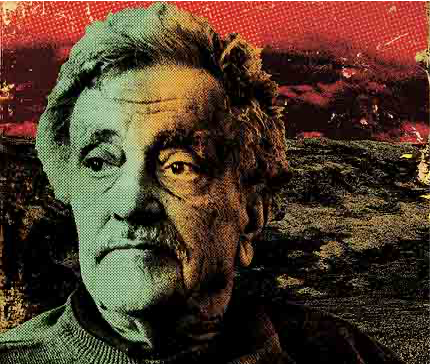

Illustration by Sean McCabe (Photo: A. Robert Johnson/Courtesy of New York Philomusica) From New York Magazine, March 26/Apr. 3, 2006

In our time, as the drums of war beat louder and faster, it’s worth revisiting a souvenir from the previous century that spans that era’s two world wars. A good introduction to this story is Alicia Zuckerman’s short interview of Kurt Vonnegut that appeared in New York Magazine’s issue dated March 26/Apr. 3, 2006:

Life During Wartime

Kurt Vonnegut talks about his “desecration” of Stravinsky’s romanticized “The Soldier’s Tale.”

In 1993, New York Philomusica commissioned Kurt Vonnegut to write a new libretto for “L’Histoire du Soldat” (“The Soldier’s Tale”), Stravinsky’s theatrical work about a violin-playing grunt’s deal with the devil. Vonnegut — the novelist was, as his readers know, a World War II prisoner of war — replaced the narration, by C. F. Ramuz, with a new text about Eddie Slovik, who in 1945 became the last American soldier to be shot for desertion. A legal fight — after a change in copyright law, the Stravinsky estate tried unsuccessfully to claim control over the new version — has kept the piece off stages for almost a decade, but it’ll be back on March 30.

*****

AZ: Tell me how you ended up with this project.

KV: Maybe 30 years ago, a small orchestra asked me if I would be the narrator for a concert, so I said, “Sure. Send me the libretto.” The story is about a soldier carrying a violin — you know, soldiers get rained on, and a violin wouldn’t have a chance, and so I thought it was just preposterous, and was somewhat troubled that this thing was premiered in 1918, during the most horrible war for soldiers in history. So I said no, thanks. Many years later I was at a party at George Plimpton’s. And Bob Johnson [the orchestra’s artistic director] was there, and I mentioned what a piece of crap I thought the narration was for “L’Histoire du Soldat.” So Plimpton said, “Oh, yeah? Why don’t you write a good one?”

AZ: Stravinsky certainly was not known for his graceful marriage of text and music.

KV: The music itself had a nasty edge — sort of a Kurt Weill sound, which was quite appropriate for 1918. I don’t think he gave a damn about the text, and the war was unthinkable, it was just so awful. The folk legend came into being maybe 100 years before. A soldier was just another guy — there wasn’t a huge war going on, modern war hadn’t begun yet. In 1918, to be a soldier was really something.

AZ: So you changed the story completely.

KV: I lucked out when I thought [of] Private Slovik. He was the only person to be executed for cowardice in the face of the enemy since the Civil War. Ike signed his death certificate. They stood him up in front of his comrades, and they shot him. [DS: The newly recruited Slovik — a small-time crook who’d just married and landed a legit job when he was drafted near the war’s end — had been thrown into battle with no preparation, so he ran from the shells blowing up around him and then told the truth to his C.O.]

AZ: In the libretto, you quote an Army manual’s execution instructions. Is that real?

KV: Yeah, oh yeah. They talk about a restraining board, in case the guy can’t stand up.

AZ: You’ve written so often from an autobiographical point of view. Did you consider doing that here?

KV: No, that would make me an asshole. I’d written enough about myself.

AZ: But it must have been visceral to write.

KV: Yes, it was. It was a unique event in American history, and “The Execution of Private Slovik,” the book, was out of print — one of the singers says “out of print.” Slovik deserves to be kept alive. If his name had been McCoy or Johnson, I don’t think he would have been shot.

AZ: When your version premiered in 1993, the country wasn’t at war. Is there anything you would change now?

KV: I don’t think I have that kind of power. What holds me down is futility. The last book to be influential was “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” And you know what Lincoln said to [Harriet Beecher Stowe]: “Are you the lady who caused this war?”

AZ: Some critics really disliked what you did. The Times critic wrote, “It was difficult not to imagine the ghosts of Stravinsky and Ramuz . . . glowering at the proceedings.”

KV: Well, it was a desecration. It was a sacred text, and I dared to fool with it. And some people just find that unbearable. That critic— I spoiled his evening.

AZ: Have you worked on other musical projects?

KV: I wrote a secular requiem, where [I say] there’s nothing to fear in the afterlife. I just had everybody sleep — ’cause I like sleep. Seymour Barab, a cellist and composer, set it to music, and we made a recording. And the director of the Manhattan Chamber Orchestra, Richard Auldon Clark, is turning a play of mine, “Happy Birthday Wanda June,” into an opera.

AZ: By the way, I hear that you don’t have a copy of the libretto anymore—that you lost yours in a fire. Do you want mine?

KV: Well . . . I got too much crap now.

“L’Histoire du Soldat” — Libretto by Kurt Vonnegut. New York Philomusica. Broadway Presbyterian Church. March 30, 2006.

*****

I was there. The concert took place in a church, a setting that suggested how far “L’Histoire” has come since 1918. That is, having begun as farce, the piece now returned as tragic Passion — thus refuting Marx’ assertion that great historical events happen twice, the first time as tragedy and the second time as farce.

The performance was excellent and I was glad I’d brought my sixteen-year-old nephew Sam Rosen, a fellow Vonnegut admirer. When the show ended, I told Sam that I was going to go grab Vonnegut before he got mobbed and did he want to come with, but he demurred. When I got to the pew where Vonnegut, dressed in an ice cream suit like his favorite writer Mark Twain, was sitting I congratulated him on how much better his version was compared to the original.

I added that the music now created an eerie effect not present in the slapstick first version, as it waltzed obliviously along while Slovik’s disaster unfolded in full view — a world so cheerfully indifferent to one human’s suffering that it gave me a chill.

After that, I remarked, "By the way, I don't read your books ... I RE-read them."

He smiled and asked gamely, "Who are you?"

"Nobody really — my name’s David Shohl, I'm a composer ..."

"Composer, eh? What do you think Stravinsky would have thought?"

"Well, I’m sorry to say it, but those stupid critics were right that he would have hated it, but for the wrong reasons. You didn't ruin his art, you redeemed it. But he wouldn't have cared — he couldn’t tolerate people messing with his stuff, especially if it involved money. A genius no question, but not exactly a mensch.

“In fact, he managed to evade all the giant wars of the century: he wrote “The Soldier's Tale” in Switzerland near the end of WWI — as you know — because the opportunist in him needed something that would be topical but apolitical, so he got that hack Ramuz to write the generic Faust libretto. He didn't give a shit about the implausible homecoming or the mediocre text, he just wanted something to hang his brilliant music on. Twenty years later, on his way to America to escape the Anschluss, Igor stopped in Italy to invite himself to lunch with Mussolini!"

Vonnegut's face registered some shock — the old WWII POW had of course endured the hell Stravinsky fled — and he replied in a subdued voice, "I didn't know that."

"Nobody does! Stravinsky managed to hush it up for the most part. But it's true, a matter of record — you can look it up.” On that note, I thanked the author again and went back to my pew.

I was glad I made Vonnegut smile but it was my nephew Sam who actually got a laugh out of him, as things turned out. To get this, you have to know that whenever a character dies in Vonnegut’s “Galapagos,” someone else is around to observe how little the person accomplished in life, since he or she "was never going to write Beethoven's Ninth Symphony" — as if it would only be regrettable if the deceased had composed a masterpiece. This is analogous of course to "So it goes," the recurring motto when characters die in “Slaughterhouse-Five” (which, incidentally, mentions Slovik), Vonnegut’s novelization of his memories of the fire-bombing of Dresden.

After I finished haranguing Vonnegut, Sam was emboldened to go up and speak to him after all, saying of Private Slovik that "It's not like that guy was going to write Beethoven's Ninth Symphony or anything," which is when Vonnegut laughed. This was especially gratifying for me because I had turned Sam on to the man's work in the first place, with “Galapagos.”

A year later, Vonnegut died of injuries sustained in a bad fall at age 84. In art as in life, he valued the existence of Eddie Slovik as much as that of any world-famous composer or writer, masterpiece or no masterpiece.

When I learned that Vonnegut’s death happened after he’d tumbled down a flight of stairs, I remembered that the same fate befalls characters in at least three of Vonnegut’s novels. I then wondered how “accidental” Vonnegut’s fall might have been, since the author’s alter ego, Kilgore Trout, also dies at the age of 84 in Vonnegut’s last novel, “Timequake” (1997). A fantasy occurred to me — if somehow I had been granted a premonition of Vonnegut’s imminent death, I could have answered his first question: “Who am I? My name is Kilgore Trout, and I’ve been writing your life. You have one year to live.”

— Reporting from NYC, December 20, 2010

Great piece! The only KV connection I could claim was exchanging nods with him at a bakery on the UWS, and I drove a Ford Galaxie in high school in homage to Andy Lieber from Breakfast of Champions

I, too was a CO in the US. 1968 the US SSS took away grad school deferments.

Draft board refused granting CO status because I wasn't part of the right religion and I said I would defend my family against attack!